To provide the best care for patients undergoing surgery, the team operating must be comfortable communicating with each other, regardless of what job they are performing. However, because of the power dynamics in medicine and other fields, it may be challenging for individuals to speak up on behalf of patients. For Advancing Health Scientist and anesthesiologist Dr. Alana Flexman, highlighting the importance of equity, diversity, and inclusion among health care workers in the operating room leads not only to a positive work environment for the operating team, but also to better care for the patient.

“In the operating room, you have to be comfortable standing up to more experienced staff in order to take care of the patient. They may not notice when something is not going according to plan during an operation and speaking up in a hierarchical setting can be difficult, especially if you are in an equity-seeking group or might feel marginalized,” said Dr. Flexman. “Standing up in an environment where an individual may feel marginalized makes it even harder. This equity work is about good patient care, operating room function, and the environments we train people in because they have a right to train in a safe space. There are so many layers of equity, diversity, and inclusion work that we are just starting to identify.”

Speaking the academic language

It was an award ceremony for the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society that started Dr. Flexman’s journey down this research path. Of the eight awards given out during this celebration, none were bestowed to women. “There was quite an outcry in the community after that occurred, and seeing that I had a leadership role in this medical society, I saw the opportunity to start making change,” she said.

Dr. Flexman attended a meeting with the goal to integrate equity among the speakers for the next event and found an enthusiastic ally in Dr. Gianni Lorello from Toronto Western Hospital at the University of Toronto.

“We had never met before, but we were both researchers, so we decided to start with advocacy and research and look at gender inequality in anesthesia. We noticed things in our environment that we weren’t happy with and thought that we can do better, became friends, and now collaborate on several different projects on equity, diversity, and inclusion,” she said. “We recognized the importance of publishing data on this topic. There is a lot of weight to that because inequity is now formally being documented.”

One of the first published articles evaluated authorship gender, specifically first authors, in the Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. This initial step in formally documenting and analyzing inequity not only showed that female authors were under-represented relative to male authors, despite more females entering the profession, it also provided evidence of inequity in a medium that academia understood — peer-reviewed journals.

“We started by simply looking at authorship gender and just documenting what was happening in our world. It’s applying the scientific method to a problem that needs solving. Our work systematically looks and documents problems,” Dr. Flexman elaborated. “Over time, you can track these changes to see if progress has been made. That’s the other good thing about doing analyses; it’s quantitative and you can look the proportion of women in leadership roles or racial diversity on an editorial board, and you follow that over time and see if progress is being made.”

Because this work is citeable, published research, not only can it be a model to follow to uncover equity, diversity, and inclusion blind spots in other areas, but it also provides data to support change. Also, this initial step can allow the work to delve deeper into why these inequities exist.

Challenges in making change

One of the most challenging hurdles to overcome when advocating for change is the hierarchical structure of medicine. This structure parallels the military, except that there are different names for different ranks. For example, on the pathway to become a staff doctor, one is first a student, then they subsequently become an intern, resident, fellow, and staff, with further ranking within each of these career stages. There is even further hierarchy between surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and support staff. But, said Dr. Flexman, this is starting to change.

A recent survey by Dr. Flexman and her colleagues aimed to evaluate experiences related to power dynamics of the operating room environment and identified groups that perceive more conflict and discrimination. The survey found that groups like women, young people, racial minorities, or sexually or gender-diverse people are more likely to both experience and witness discrimination.

“This is important to consider,” Dr. Flexman explained. “Because if you want to move up the ranks, there are always people above you who can have significant influence over achieving your career goals — references are a crucial component in securing a job and medical specialties are small, tight-knit communities. For that reason, training positions are more vulnerable to abuse and harassment. So yes, a trainee can stand up in an operating room in front of everybody, but if they are trying to get a job at that institution this could be very daunting, even more so if they are in an already marginalized group.”

Even though most people objectively think that it’s not right that certain demographics dominate leadership positions, Dr. Flexman mentioned that it can be challenging to re-distribute power because it is “uncomfortable”, but, she said, being uncomfortable is a good thing. “Change is very uncomfortable, but if you are not uncomfortable then you are not challenging the status quo enough — not challenging the power dynamics that really need to change. It’s an uncomfortable thing to talk about, but making this change towards a safe, communicative environment for all medical staff is critical to improving the care of patients.”

Communication is crucial for patient care

For example, during an operation, the operating team members are responsible for balancing a variety of factors to maintain a patient’s safety while undergoing surgery. However, negative interactions can influence the team dynamic and potentially cause harm. For example, if a person has recently experienced rudeness or discrimination, they may not feel as comfortable asking for clarification or communicate as readily.

Communication disruption has been analyzed in a study that assessed rudeness and its effect on how the operating team functioned. The team that experienced rudeness, where an external expert’s comments included mildly rude statements completely unrelated to the team’s performance, performed worse and missed several important metrics when treating patients compared with the team that did not experience rudeness, whereby the external expert provided neutral comments. The most significant issue was that, after experiencing rudeness, the team communicated and shared information with each other less, which can put the patient at risk.

“If an operating team feels tension or has experienced a negative environment, everyone becomes quiet and then information may not be shared,” said Dr. Flexman, who has been practicing anesthesiology for over 12 years. “This is not great for the patient. We need to empower everyone in that operating room to speak up and that means making it a psychologically supportive environment for people to do their best. I think things are changing for the better, because overt behaviour that was tolerated even ten years ago is no longer acceptable and that continues to improve.”

Time to change

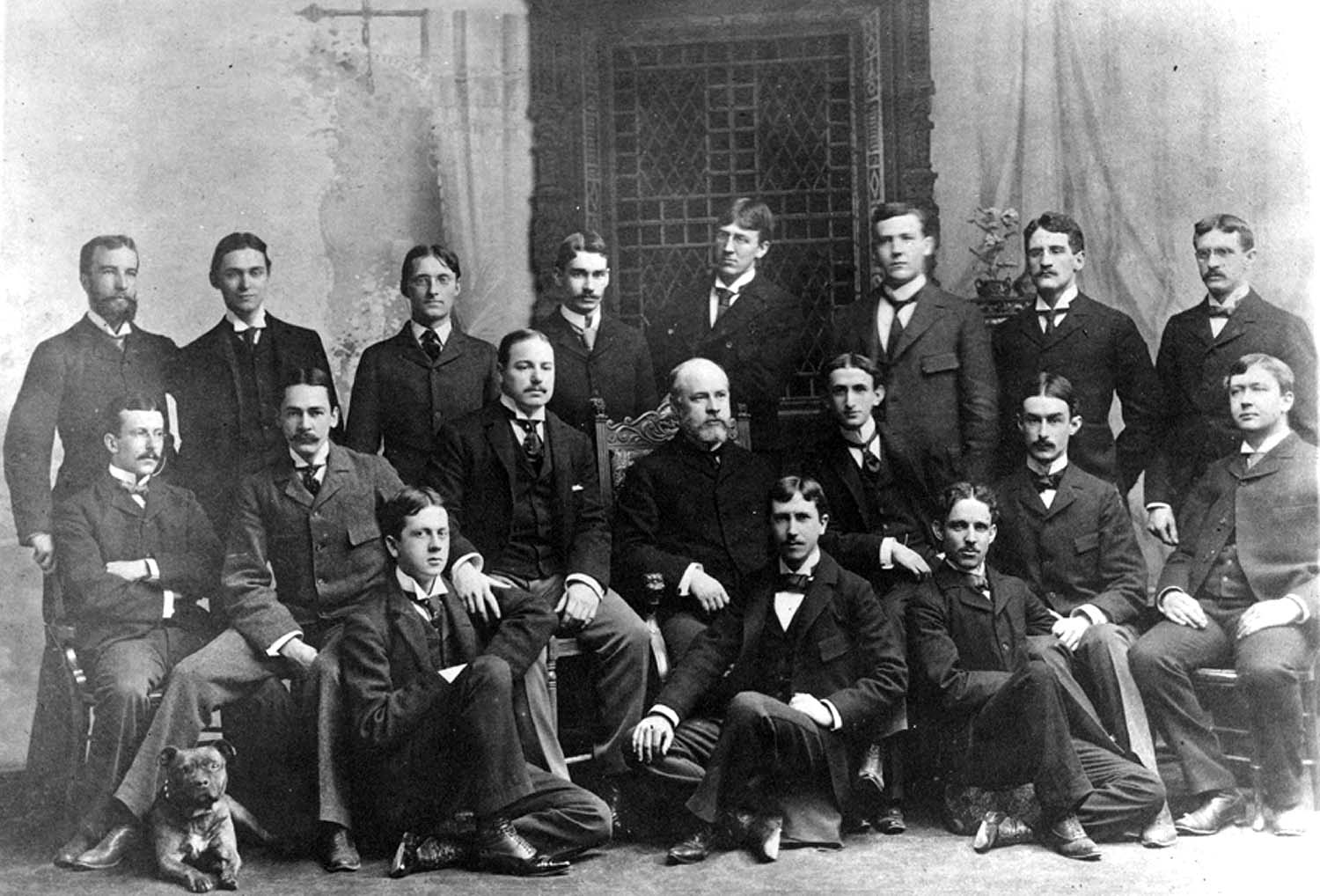

Historically, science and medicine has not been inclusive. When walking along the hallways of medical schools displaying graduating classes, it is clear that most people have been excluded. Now, medical institutions are actively working towards training and employing different types of people. This is an important step because it begins to chip away at the problem, not only because it gives anyone who wants to work within health care a fair opportunity, but there is a growing body of evidence that diversity in health care providers improves patient care.

An example of this is patient and provider concordance, which means that if patients and health care providers are the same gender or race, research shows that patient outcomes often improve. In a recent study evaluating outcomes in common surgery procedures, female patients had worse outcomes when treated by male surgeons than when treated by female surgeons. This trend was not observed in male patients treated by female surgeons.

“People didn’t expect to see that provider and patient concordance would have such an impact. We don’t know why it happens, but it’s something that we are working to understand,” said Dr. Flexman. “We are diversifying the workforce over time, it’s slow and it’s skewed, because as you go up the hierarchy, there is less and less gender and racial diversity, but we are diversifying and that does have an impact. It’s a start.”

Future work

An important aspect of diversifying the workforce is looking at the diversity within different medical school training programs. Dr. Flexman is currently working on a project as a follow-up to her work evaluating disparities in the residency matching. “We surveyed all the program directors in Canada for every specialty and received their demographics. It’s an interesting snapshot of training in Canada and also of who is doing the training. Plus, program directors have a lot of jurisdiction over the selection process and training environment.”

Dr. Flexman and her colleagues looked at representation across those different programs and whether or not they had optimistic, pessimistic, or neutral feelings towards workplace diversity within their specialty.

“When observing medicine as a whole, we noticed that there were big disparities in the demographics of the various specialties. We want to understand why, because it’s not random,” she said.

Although this study is still in progress, Dr. Flexman was able to share some promising news: “Physicians are more optimistic about workplace diversity in their profession compared with other workplaces.”

Unlike her perioperative stroke research, Dr. Flexman and her colleagues do not receive funding for their equity, diversity, and inclusion research, which can often be a barrier to conducting this type of work. However, that doesn’t mean it’s less meaningful to her. “It’s work I do that I get meaning from, and I can apply the skills I gain from doing this to other elements of my working environment. I also want to make a difference to positively affect the lives of my colleagues, particularly trainees, my patients, and future colleagues and patients,” she said.