Patient engagement is far more than ticking a box showing that patients are present when decisions are being made. Patients’ input is valuable to inform how health care can better serve them by understanding their values, needs, and preferences. This includes enabling inclusive, accessible, and appropriate experiences for people interacting with health care systems and welcoming those who may have previously avoided them. The end goal of this effort is to ensure that all voices are heard, respected, and valued. Health care exists to support patients, so meaningful engagement with patients with non-dominant identities should happen in respectful, appropriate, and empowering ways to positively impact decisions relating to programs and services that affect them.

In a recently published article, Advancing Health Program Head of Evaluation Dr. Beth Snow emphasizes how engaging people in planning and evaluating health care programs and services needs to go beyond equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), and highlights three important aspects to consider:

- Patient engagement often systematically excludes populations experiencing oppression

- Silencing and delegitimizing these populations further entrenches health inequities

- Intersectionality (multiple factors of advantage and disadvantage, ex. gender, race, class, etc) helps unpack and disrupt systemic issues and power relations involved

Defining diversity and intersectionality

With several fields moving towards improving EDI, diversity is often brought to the forefront. Sometimes, this includes focusing on people with non-dominant identities who are present, or not present in decision-making and leadership spaces. But, Dr. Snow says that spotlighting non-dominant groups as a way to improve diversity “can implicitly suggest that ‘dominant’ traits are ‘normal’ and everything else is ‘other’.”

However, diversity itself is not hierarchical, it is relational. In the article, Dr. Snow quotes Dr. Vidhya Shanker who describes diversity as “a random assortment of essentialized identities — lateral as opposed to hierarchical differences.” Dr. Snow summarizes, “A person on their own can’t be ‘diverse’, because diversity is a characteristic of groups, not of individuals. A single person is not diverse on their own, it is more about what they have or do not have in common in relation with others. In the current environment, the implied definition of ‘diverse people’ is that they are not the ‘standard’. By referring to individuals as ‘diverse’, the unstated is that dominant traits (white, cis, male, etc.) are considered ‘normal’, everything else is ‘other’. Moreover, there is far more to EDI than having people of varying backgrounds, sexual orientations, and abilities at the table.”

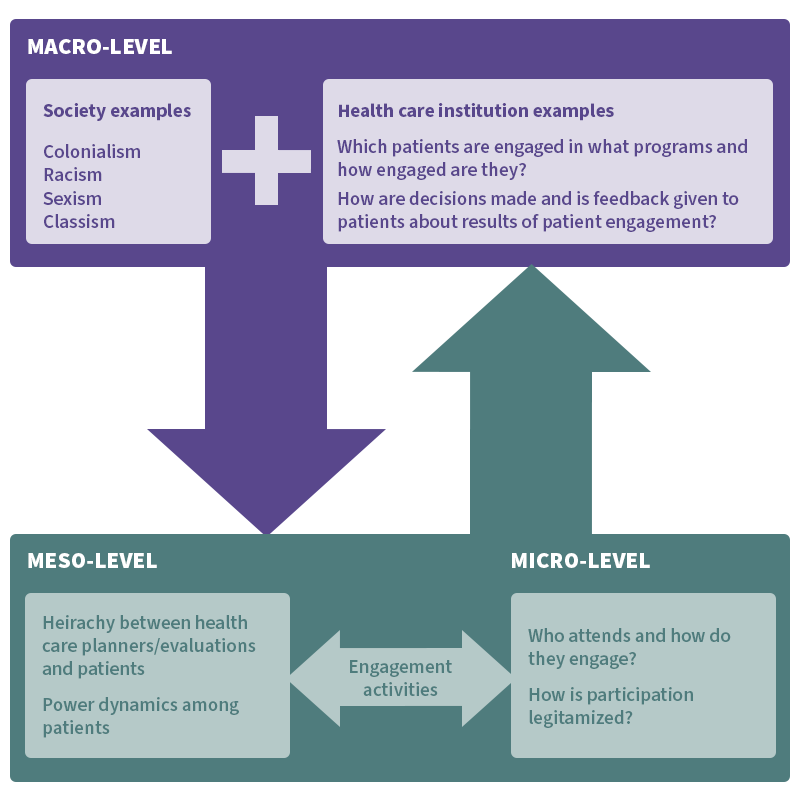

Another important concept that links closely with diversity to create accessible and meaningful patient engagement experiences is intersectionality. Intersectionality is defined as the interconnected nature of social categories (race, class, gender, etc.) that create overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. Within the context of Dr. Snow’s paper, “critical inquiry of patient engagement through an intersectional lens requires consideration of the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels of patient engagement, and how power dynamics operate within and across each of these levels.”

In other words, meaningful patient engagement needs to consider how societal discrimination (racism, sexism, etc.) and power dynamics affect how patients interact with health care systems and how they affect patient engagement processes.

The diagram below, adapted from the journal article, shows the different power dynamics (macro-, meso-, and micro-) that exist within the health care planning space.

Presence does not equal engagement

As emphasized at the beginning of this article, patients’ input is valuable to empower them to make well-informed decisions on health care about programs, services, and systems that will influence future health care. This means not only respecting and valuing their voice, but importantly, giving patients decision-making power when they are included in planning and evaluating processes.

“In meaningful patient engagement, patients are there to contribute and make a difference. It’s not just being present, but also about being actually listened to and considered and the acknowledgement that their opinions are legitimate,” emphasized Dr. Snow. “Genuinely including patients is different from just having them merely present at the table. If decisions being made are no different than they would have been if patients weren’t present, then meaningful patient engagement has probably not happened.”

In fact, inviting patients to participate in health system decision-making processes and then not listening to their input does harm. This is especially pertinent to patients who have experienced discrimination or oppression when seeking care. Dr. Snow elaborates, “If you bring people in under the guise of valuing their word, but then dismiss what they say and don’t listen to them, you are just reproducing the oppression or discrimination. This can be especially damaging when not considering and attending to the power dynamics in these discussion spaces and this does harm.”

Power at play

Two of the most important aspects to contemplate when considering patient engagement are power relations and power dynamics.

“Power is at play at every single step [in patient engagement] and this is further emphasized for people experiencing oppression and discrimination. We need to think deeply about power and privilege and how power works at different levels, how it’s pervasive and can be used intentionally and unintentionally to silence or to exclude people.”

Stimulating systemic change

Patient engagement is not new. In fact, there are several organizations that focus on connecting patients with decision-makers and researchers throughout the health sector to be involved in various health initiatives and research projects. But often the patients who become involved are those who are easy to recruit because they are willing and able to engage on the terms set by the health care system. “These are patients who are already connected and often are already privileged,” highlighted Dr. Snow. “These are not the patients that are experiencing discrimination and oppression because patients already engaged with the health care system are the easiest for decision-makers and researchers to recruit and work with.”

Patients that feel unsafe, oppressed, or discriminated against likely won’t seek opportunities to be in an environment where they will relive those experiences. Harrowing examples within the B.C. health care system came to light with the In Plain Sight report, published in 2020, which collected experiences from thousands of voices about the rampant racism against Indigenous Peoples.

Despite Canada’s status as a country with universal health care, not everyone has the same level of access and the same level of cultural safety. Dr. Snow challenges health care organizations and policy-makers to make substantial changes in their processes, structure, and culture to make patient engagement meaningful and successful. This involves reflecting on what needs to be done differently, what recruitment strategies need to change, whose voices are missing from these conversations, and which voices are being actively excluded and discriminated against. The big question: How to meaningfully reach and support people who haven’t been reached before in a way that supports their engagement to stimulate genuine change?

Resources to get started

Thankfully, there are resources to help. Dr. Snow created a model to engage patients who are not traditionally heard in health care planning. There is a handbook illustrating concepts and a workbook to go through with processes to plan and then execute patient engagement, ensuring it is safer and more inclusive. It is important to note that these materials were written several years ago and need to be updated to include trans-friendly language.

These resources were also transformed into an online one-hour course available on the Provincial Health Service Authority’s Learning Hub. Sign-up is free and once logged in, you can search for the course “Heard and Valued: Engaging Marginalized Populations”.

If you would like to read Dr. Snow’s article Patient engagement in health care planning and evaluation: A call for social justice please email her at bsnow [at] advancinghealth.ubc.ca.