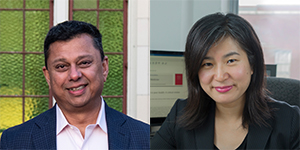

Advancing Health Director Dr. Aslam Anis and Program Head for Health Economics Dr. Wei Zhang have co-authored work to guide policymakers around the world towards the optimal approach in determining reimbursement prices for generic drugs.

Generic drugs are an important feature of public drug plans, and aim to improve access to prescription medicines, particularly for people who may otherwise struggle to afford them. Whether the cost of drugs is paid by a private or public insurance plan, determining how much insurers should pay for generic drugs is vital in order to maintain accessibility and reliability of the prescription drug supply. A common approach is to set the maximum reimbursement price as a percentage of the price of the branded drug. In many countries this percentage depends on how many generic options there are for a drug, a model called “tiered pricing.”

In 2014, a tiered-pricing framework (TPF) was introduced across Canada in an attempt to reduce drug costs, accelerate the entry of generics into public drug plans, and subsequently improve access to much-needed treatment options. Previous Advancing Health-led research showed that TPF is an effective method of regulating the price of generic drugs in Canada, facilitating patient access to drugs, and increasing market competition. It also suggested that a similar framework could be of benefit to a number of countries across the globe.

As a follow up to this finding, Drs. Anis and Zhang joined researchers from the Universities of Alberta and Toronto to investigate how different pricing schemes work in different market environments around the world and suggest policy implications. Different pricing schemes use a variety of reimbursement percentages. For example, in Canada the cap is 75 per cent of the brand price if there is one generic firm selling the drug; 50 per cent if there are two generics; and 25 per cent if there are three or more generics. Austria and South Korea use similar schemes with slightly different reimbursement percentages.

Using simulation models, the researchers analyzed the effect of different tiers on two outcomes of interest: the average price paid by insurers for all generic drugs available in the drug plan formulary and the number of suppliers of each generic drug. The number of suppliers is important because too few can increase the risk of drug shortages but too many can add excessive cost to the system.

Published in Value in Health, the results give policymakers specific, empirical guidance on setting tiers to improve overall societal welfare and lower prices of generic drugs based on the characteristics of the country or region.

The analysis suggests that there should be at least two and at most four tiers, with more tiers in larger markets. The team also found that tiers should not be closely bunched together: 65 per cent and 30 per cent are likely to perform better than 50 per cent and 45 per cent, for example.

“When striving to align policies with the best possible outcomes for patients, it’s essential to understand the impact of tier structures on the entry of new generic providers to the market, and ultimately, on the availability and accessibility of these medications to the public,” said Dr. Anis.

Co-authors include Drs. Javad Moradpour and Aidan Hollis from the University of Calgary, and Dr. Paul Grootendorst from the University of Toronto.